What are the requirements for bolt tightening torque when installing large flanges for construction machinery parts?

Release Time : 2025-12-03

When installing large flanges in engineering machinery, the bolt tightening torque is a core parameter ensuring sealing reliability and structural stability. Its setting requires comprehensive consideration of flange structural characteristics, bolt strength grade, gasket type, media conditions, and sealing requirements. Precise torque control is achieved through scientific calculation and standardized operation.

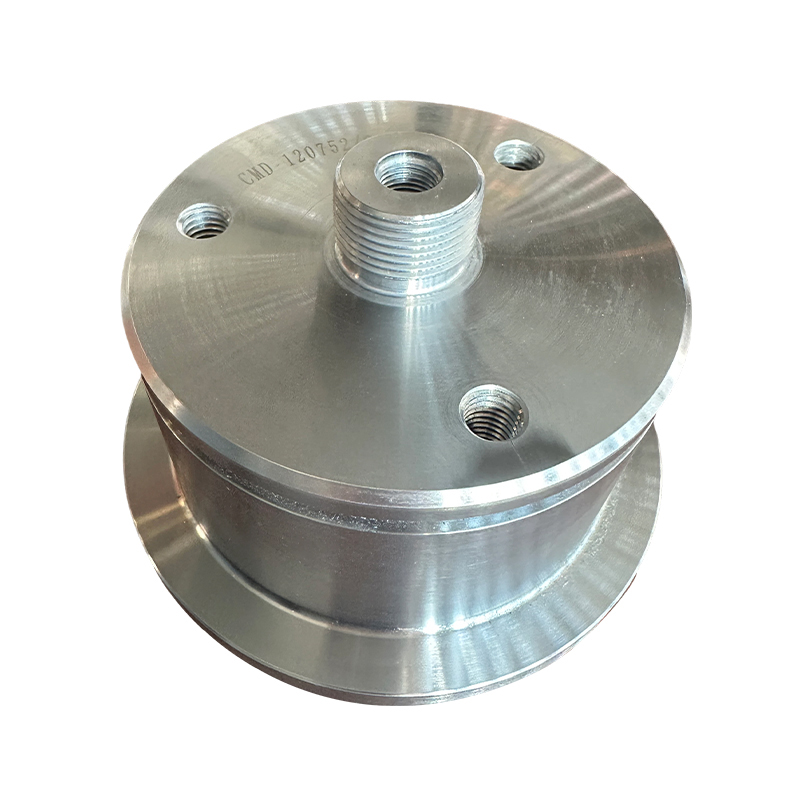

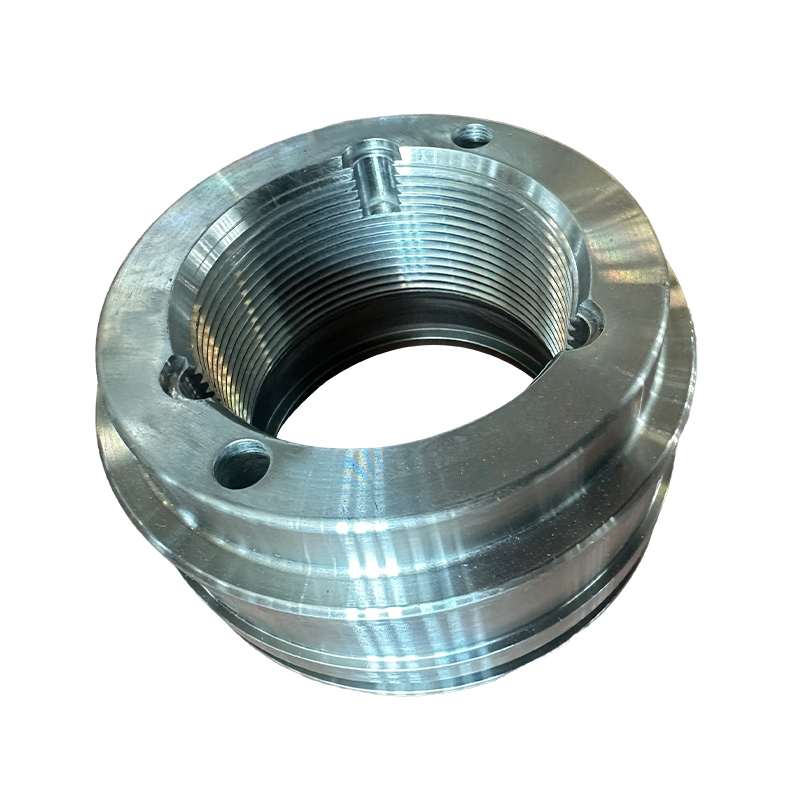

The flange's geometry and structural form directly affect the distribution of bolt torque. Large flanges, due to their larger diameter, require more bolts to evenly distribute the load and avoid localized stress concentration. For example, high-pressure pipeline flanges may have dozens of bolts, and the torque of each bolt needs to be adjusted differently based on its position on the flange (e.g., radial, circumferential) to ensure uniform stress on the flange surface. Furthermore, the flange's sealing surface type (e.g., raised face, recessed face, tongue and groove) also affects gasket compression, thus requiring different initial torques. For example, tongue and groove flanges, due to their high sealing precision, typically require stricter torque control to prevent gasket misalignment.

The bolt strength grade and material are fundamental to determining the tightening torque. High-strength bolts (such as grade 10.9 and 12.9) have high tensile strength and can withstand greater preload, but overtightening must be avoided to prevent yielding or breakage. For example, the recommended torque for grade 10.9 bolts is usually higher than that for grade 8.8 bolts, but the theoretical torque needs to be converted to the practical operating value using a torque coefficient (usually 0.11~0.15). Regarding materials, stainless steel bolts have a lower modulus of elasticity, resulting in greater deformation under the same torque, requiring a reduction in torque to prevent excessive compression of the gasket; while carbon steel bolts can be tightened to the standard torque.

The required tightening torque varies significantly depending on the type of gasket. Metal spiral wound gaskets, due to their higher rigidity, require higher torque to achieve a seal; while rubber or flexible graphite gaskets, being easily compressible, require a reduction in torque to prevent excessive compression and failure. For example, in chemical pipelines, metal spiral wound gaskets may need to be tightened gradually in stages to the final torque, while rubber gaskets may be tightened in a single step to a lower torque. In addition, parameters such as gasket thickness and width also affect the sealing pressure, requiring calculation to determine the optimal torque range.

The operating conditions of the medium are a key factor in adjusting the tightening torque. High-temperature environments cause thermal expansion of the bolt material, reducing the preload; therefore, the torque needs to be increased appropriately in the cold state to compensate for heat loss. Low-temperature environments may cause material contraction, requiring a reduction in torque to prevent bolt breakage. High-pressure media increase the separation force on the flange seal, necessitating increased torque to enhance sealing performance. Corrosive media require consideration of the bolt's corrosion resistance to avoid torque attenuation due to corrosion. For example, large flanges on offshore platforms, subjected to long-term salt spray corrosion, require periodic retightening of bolts and appropriate increases in initial torque.

The standardization of the tightening process directly affects the final torque effect. A symmetrical cross-tightening method is typically used, that is, tightening the bolts gradually in stages along a diagonal sequence to ensure parallel closure of the flange faces. For example, the first stage tightens to 50% torque, the second stage to 80%, and the third stage to 100%, with the flange clearance checked for uniformity at each stage. For high-temperature and high-pressure flanges, hot tightening is necessary after heating to compensate for preload loss due to thermal expansion. Furthermore, using a high-precision torque wrench or hydraulic tensioner can reduce human error and ensure that the torque deviation of each bolt is controlled within ±5%.

Regular monitoring and maintenance are essential measures to ensure long-term sealing performance. Ultrasonic testing and torque retightening can promptly detect bolt preload decay or gasket aging. For example, in petrochemical plants, large flange bolts typically need to be retightened to the specified torque after a certain number of operating cycles, and historical data is recorded to analyze decay patterns. For critical equipment, torque sensors can be installed to monitor bolt status in real time and provide early warnings of potential leakage risks.